by Boaz Bismuth – Israel Hayom

At the end of last weekend, the Jewish world – some might say the entire world – marked 25 years since the passing of the Lubavitcher rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh and thus far the last leader of the hassidic dynasty. In the quarter-century that has passed since his death, Chabad has become a force of nature in the Jewish world, an immense draw for religious, secular, hassidic, and ultra-Orthodox Jews, and even heads of state.

His presence only grows stronger. The archive of video and audio recordings he left behind continue to nurture the next generations, but they don’t need the visual experience. Neither do they need the famous portrait of the rebbe that hangs in millions of Jewish homes and has already become an international cultural icon. The rebbe is still, and apparently will always be, the lifeblood of Chabad. But he doesn’t belong to Chabadniks alone, and his influence in numerous areas continues to increase.

The Chabad hassidic sect seeks to emphasize that it is a general “Jewish home” and categorically rejects political involvement. But its army of “diplomats” – thousands of emissaries in hundreds of countries – are making it into a major political force. Last Monday, hours after I landed in New York, I was already visiting the Lubavitcher rebbe’s gravesite. Despite the late hour, dozens of Jews and gentiles were there. They came to plea, to pray, to wonder, to sense the atmosphere. There were Sanz, Vizhnitz, and Bobov Hassidim, and even a few from Satmar, alongside traditional Jews, Modern Orthodox Jews, and young secular Jewish boys and girls dressed scantily, as well as a young African American woman with a special supplication.

The next day, at 770 Eastern Parkway in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, known as “770” and the center of the world Chabad movement, I encounter Mendel Alperowitz, a new Chabad emissary in South Dakota, who has extended Chabad’s presence to all 50 US states. He was with the emissary from Alaska, Mendy Greenberg. The emissaries to the northern state are nicknamed “The Frozen Chosen.”

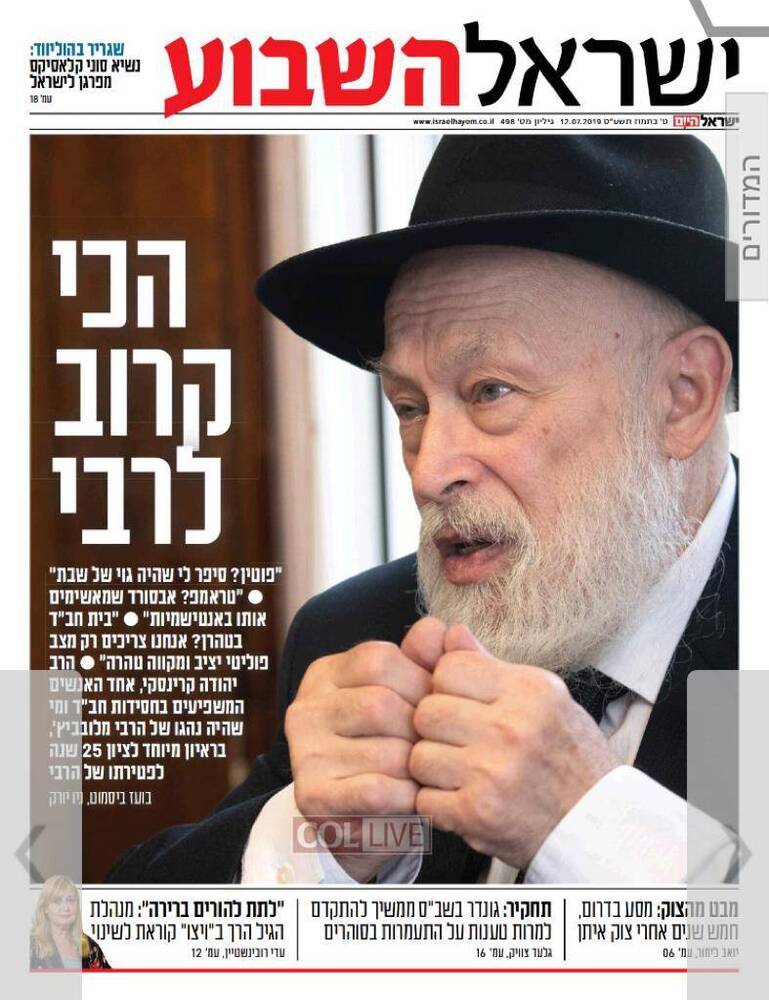

In a modest room, Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, chairman of the educational arm of the World Chabad movement, awaits me. He started off as an emissary of the rebbe in the 1950s, when he was sent to provide encouragement to Kfar Chabad after a terrorist attack at a school there killed six people. Later, he served as the rebbe’s personal chauffeur, and then as his spokesman. Today, at 86, he holds the highest position in the hassidic sect but he remains behind the memory of the rebbe. Chabad opts to write its future with the ink of the past, and the past, for Chabad, provides inspiration for the future.

Rabbi Krinsky grew up in a Chabad family, the son of parents who arrived in the US at the start of the 20th century.

“My parents made a vow between them that if God would bless them with children, they would do everything they could possibly, and more than possibly, do to see that they were ‘shomrei Torah ve’mitzvot’ [observant Jews.] And they succeeded. They built a very Jewish home in Boston. I’m the youngest of nine children. When the previous rebbe in the ’20s and ’30s would send the ‘shluchim’ [emissaries] from Russia and Poland to America, they would always stay with us. So I grew up in this kind of warmth, ‘hachnasas orchim’ [hospitality], davening, learning. I was going to public school. There were no yeshivas, no Jewish schools in America.”

Rabbi Krinsky is clearly completely devoted to the Rebbe.

How fortunate he is to have worked so closely with the Rebbe.

I hope he writes a book.

Beautiful!!!